CHARLIE WALL: THE BOLITA KINGPIN

Hollywood screenwriters dare not dream up a more improbable script: Descendent of blue blood pioneer Southern family rebels against wicked stepmother, is expelled from military school and seeks refuge in the exotic immigrant quarter, where he becomes prince of the underworld. Along the way, the character kicks his morphine habit, fixes elections, and dodges bullets with his name on them. Yet he is generous and compassionate with orphaned children.

Naysayers may excuse the script as steeped in Hollywood B, but it is all true. Our hero, or anti-hero, is Charlie Wall, whose life reads like a character from the seamy world of Tennessee Williams rather than the underworld of Vito Corleone.

Wall was born in Tampa in 1880. The son of a distinguished physician and civic leader John P. Wall, Charlie seemed destined for a brilliant political or legal career. But unfortunately, a stormy youth and family tragedy sidetracked him, culminating in the shooting of his stepmother and his expulsion from military school for visiting a brothel.

For reasons that psychobiographers might better explain, Charlie broke from the flock to become a black sheep. Worse, he spent his formative years frequenting the gambling tables of Ybor City and West Tampa. A mathematical wizard, he was fascinated by the magic of probability. Then, beginning in the early 20th century, Charlie Wall grasped control of Cigar City’s most profitable enterprise: bolita. He would remain in control of the numbers racket game for nearly 25 years.

Introduced to Ybor City in the 1880s, bolita (literally meaning “little ball”) quickly expanded its domain; bolita peddlers soon trafficked chances in Hyde Park, downtown, and the Scrub. With its 80:1 payoff, a bolita chance offered hardscrabble Tampa an elusive hope.

One theory holds that until Wall seized control, bolita profits returned to Cuba. With his familial and political contacts at the local and state levels, Wall ensured the reinvestment of a locally owned enterprise. As President Lyndon Johnson once exclaimed of J. Edgar Hoover when asked why he tolerated the FBI chief, “it’s better to have him on the inside pissin’ out, then on the outside pissin’ in!” Tampa may have adopted a similar philosophical attitude about Charlie Wall.

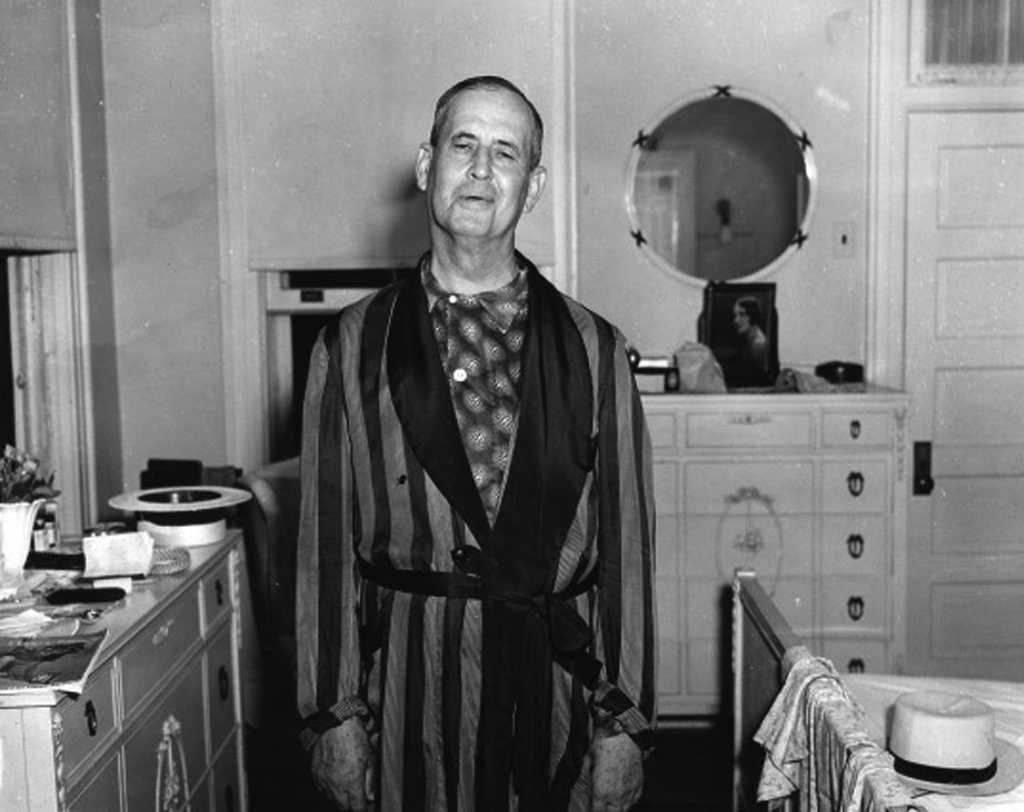

Standing 6’2″, Wall was an imposing figure. In 1912, a crusading Jacksonville newspaper profiled his power base. “Tampa is reeking in crime, and gamblers operate openly. Tampa is the most wicked city in the U.S.”

Bolita existed because the public desired it, civic authorities tolerated it, and the police department allowed it. Rampant corruption pervaded the city because of bolita’s profits. To assure compliance, Wall bestowed lavish gifts upon elected officials. In the process, he became a political force – wheeling and dealing, brokering votes, and associating with senators and judges.

Wall told a 1938 grand jury that the devil took care of him. His Faustian bargain protected him from rival bids: On a dozen occasions, he dodged assassins’ bullets. And what dons could not do, morphine nearly did. Wall became addicted to the drug, only to conquer his weakness after harrowing dry out.

In the late 1930s, Wall gracefully backed away from the hurly-burly of gambling, whoring, and bootlegging. A bloodbath ensued as rival factions grappled to control the lucrative vice economy.

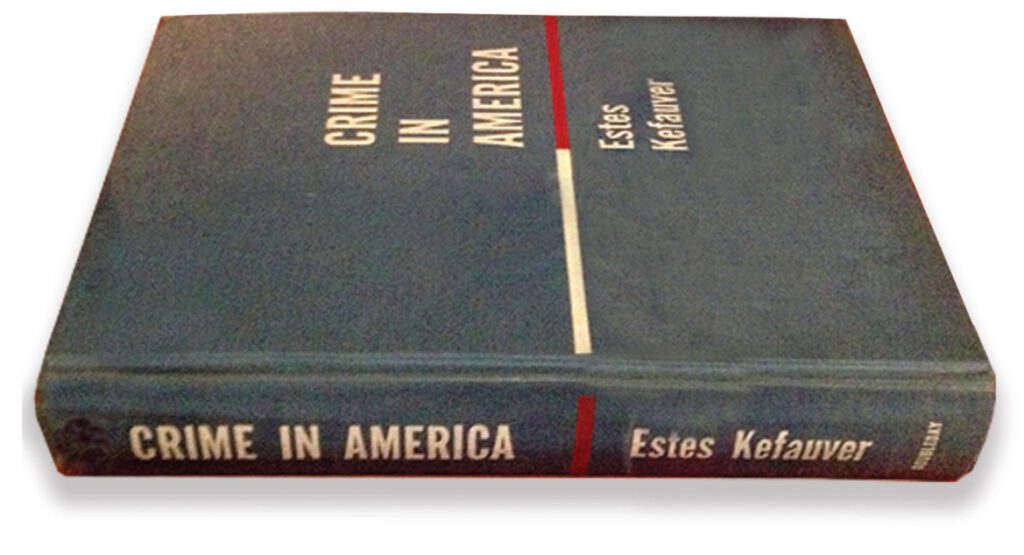

In 1950, even the most jaded Tampan must have gasped as Wall emerged from retirement to testify at the Kefauver Hearings on Organized Crime. Described as the elder statesman of bolita,” he captivated the imposing inquisitors, graphically detailing Tampa’s criminal network.

On one April night in 1955, Charlie Wall’s luck ran out. One or more assassins brutalized the 75-year-old legend, bludgeoning his head with a baseball bat and slitting his throat. Police discovered a curious relic resting on Wall’s bead stand: Crime in America by Estes Kefauver.

Gary R. Mormino, the Frank E. Duckwall Professor of History, is co-director of the Florida Studies Program at USF St. Petersburg. He is a prolific writer and author of a wide range of academic and popular books including The Immigrant World of Ybor City. He has written for the St. Petersburg Times (now The Tampa Bay Times), Orlando Sentinel, and Miami Herald. He wrote a bi-weekly column on state and local history for the former Tampa Tribune.