SLEEPING WITH THE ENEMY

What could the deal have been?

Tampa was one of many cities Castro visited in 1955. He also stopped in New York, Union (N.J.), Hartford, Key West, Miami, and many other cities with large Cuban populations. He founded a branch of his 26th of July Movement in each city. The purpose of each chapter was to raise money and collect supplies for the revolution that would overthrow Batista. Supplies consisted of clothes, food, medicine, and guns. Throughout Castro’s revolution, Tampa was linked to numerous gun smuggling operations.

In 1957, the Philomar III, a yacht loaded with arms and military uniforms to be delivered to Castro’s revolutionary army, was seized by U.S. agents off the Florida Keys. The boat was purchased in Tampa.

In 1958, another yacht, The Harpoon, loaded with arms, was seized at Port Everglades, Florida. Four Cubans who lived in Tampa were among the 33 arrested.

Also in 1958, a small vessel packed with arms, El Orion, was seized off the lower Texas Gulf Coast. Among the 36 Cubans arrested were three Cubans from Tampa.

Except for Victoriano Manteiga, founder of La Gaceta newspaper and founding president of Tampa’s 26th of July Movement, no Tampa reporter knew more about Castro’s revolution than Tom Durkin, who covered the revolution from Cuba as a photojournalist for the St. Petersburg Times and La Gaceta. According to a Durkin article published in the St. Petersburg Times on January 9, 1959, “One U.S. sympathizer even offered to provide the rebels a small submarine for sneaking weapons to Castro. The cautious Ybor group rejected his offer ‘because we didn’t know where it came from.’… Admitted by Ybor Castro supporters, but anonymously, is that 150 machine guns seized in Miami last year, packed in oil drums, passed through Tampa. An obsolete U.S. bomber, seized at Fort Lauderdale as weapons were being loaded, originated its flight in Tampa. Among those arrested were four Tampans from Ybor City.”

Did Clifton and the Sheriff’s Office directly provide Castro or Castro’s Tampa-based revolutionaries with guns? Or, they helped introduce the Tampa revolutionaries to gun dealers. Or, maybe Durkin provided the best clue as to what the deal could have been when he wrote in his 1959 article, “Despite all the activity in Tampa, Tampa Customs and Border Patrol officials report no actual arms seizures in this area.”

Perhaps Clifton and the Sheriff’s Office agreed to look the other way. But, considering the number of informants and snitches, Clifton said he and the Sheriff’s Office had, it is hard to believe that law enforcement would not know about the multiple arms shipments originating or passing through Tampa. But, with Clifton gone, we’ll never know the answer.

Whatever the deal was, did it work?

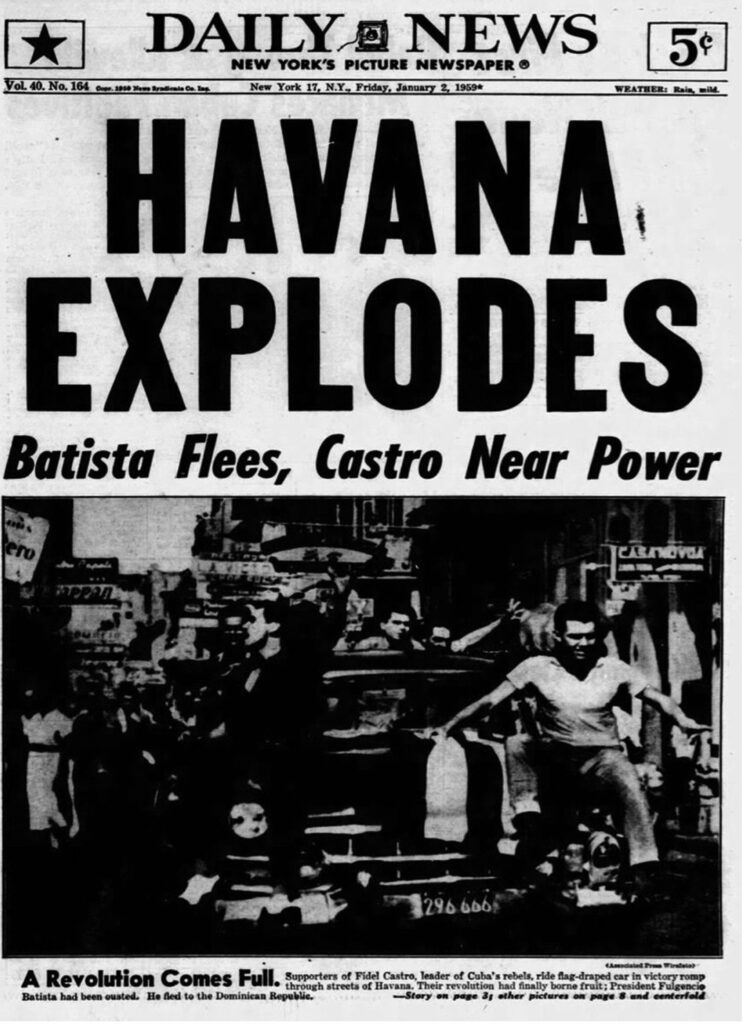

When Batista fled Cuba on January 1, 1959, numerous mafia bosses who ran casinos in Cuba escaped the island. Castro repeatedly stated throughout the revolution that when he overthrew Batista, he would shut down the casinos and imprison any criminals that remained in Cuba. Some gangsters fled so quickly that they left behind millions of dollars in cash. Trafficante stayed in Cuba.

Some historians have noted that Trafficante contributed money to Castro’s revolution, believing Castro would allow him to continue to run his casinos. Other historians have written that Trafficante thought Castro would come around once he realized how much money the casinos generated. Others claim he stayed in Cuba because the New York City District Attorney’s Office was investigating Trafficante for the murder of Albert Anastasia, the boss of what would later become known as the Gambino crime family.

When Castro learned that Trafficante was still in Cuba, he had him arrested, imprisoned, and slated for execution.

Victoriano Manteiga, a friend of both Trafficante’s and Castro’s, called Castro personally and pleaded with him to release Trafficante but failed. A handful of Tampa Cubans also made a trip to Cuba to free Trafficante, but they also failed.

Trafficante’s attorney, Frank Ragano, wrote in his book Mob Lawyer that he brokered the deal for Trafficante’s release. Not so, said Clifton, who claimed that Trafficante brokered his own release and that the Cuban government arranged for Clifton to pick up Trafficante from the airport on August 18, 1959.

“I cut a deal with a Cuban official from National Airlines and another with the Immigration Department. The Sheriff’s Office had contact with a man who was chief of the Cuban Air Force, and the sergeant in my department talked to him at least once a week to find out Santo’s status and when he was getting out,” explained Clifton. “So one night, around 12:30 A.M., I got a phone call from National Airlines and the Immigration Department saying they had put Trafficante on a plane and he would be landing in Florida soon.”