TAMPA MAFIA TAKEOVER OF THE ‘BURG’

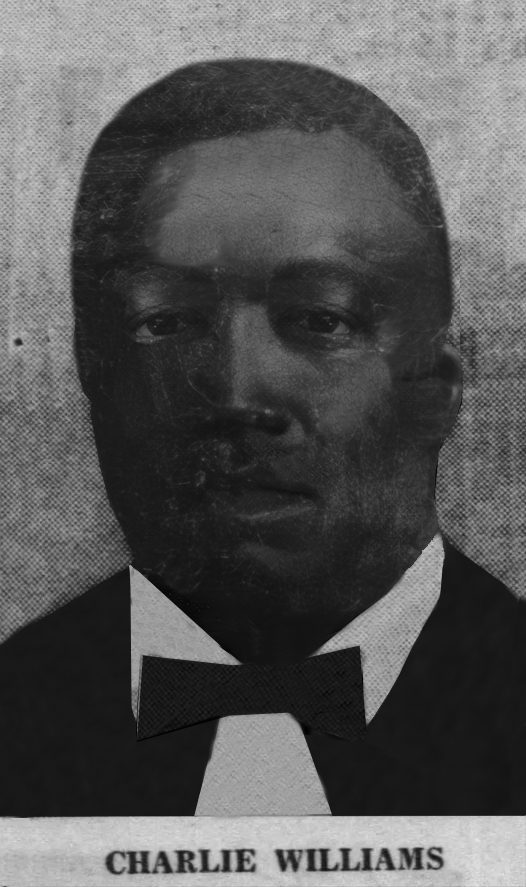

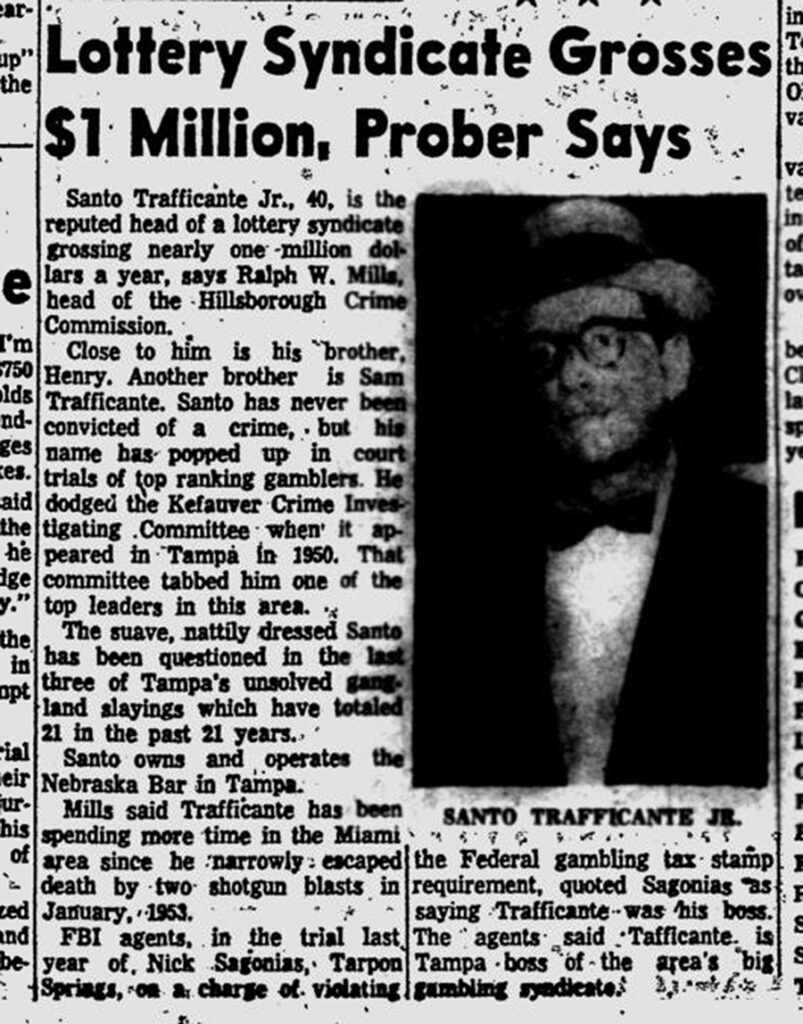

When bolita kingpin Charlie Williams was killed in Ybor City in February of 1953, local control of the bolita rackets in the ‘burg ended. While Williams was able to grow his business with little influence from Tampa at first, he started working more and more with wise guys from across the Bay. Former St. Petersburg Police Chief E. Wilson Purdy concurred, “Bolita was big business in St. Pete, but it was controlled out of Tampa.” And though it was not known why the order to take out Williams was given, it became clear that the primary beneficiary of the demise of the bolita man was Santo Trafficante Jr.

With only a few years under his belt as a Mafia boss, Trafficante Jr. was solidifying his hold over the Tampa rackets and finishing an intra-crime family war with remnants of the Italiano-Lumia faction. It was a prime opportunity to make a move into St. Petersburg to expand operations and profits. As was the custom in Tampa, Santo Jr. knew that he needed to not only pick up with Williams’ old police contacts but work towards bringing in some higher-ups in the police department to act as protectors and inside sources on law enforcement activities as his bolita expansion began.

At 9:00 PM on Feb 18, 1953, Williams was leaving a barbershop in Ybor City. As he crossed the street, a gunman approached him and shot him twice in the chest. His killing was likely part of the internal mob strife that was going on at the time about control of the rackets (Santo Trafficante Jr. was shot just a few weeks earlier).

Williams’ funeral was at the Bethel AME church in downtown St. Petersburg.

Harry Dietrich was a well-respected detective in St. Petersburg. An avid fisherman, Dietrich was also dedicated to his job in law enforcement. His area of expertise was bolita. Following the killing of Charlie Williams, the St. Petersburg police had an inclination that the Tampa Mafia would make a more significant move into Pinellas. Dietrich was in a perfect position to infiltrate the new kingpins before they had a chance to get settled.

With the word out that Dietrich was open to working with the new kingpins in town, he received a call from Tampa on January 1, 1954. The call came from Henry Trafficante. He was driving down to St. Pete and wanted to meet with the detective. The game was on. Scrambling to set the operation in motion, Dietrich agreed and went to work. He was wired with a primitive recording device for his face-to-face meeting with Henry Trafficante. Dietrich later recounted that the recorder was “inside my coat, and a wire ran from the recorder down my sleeve to the mike.” At that first meeting, after some initial niceties, during which Henry noted that Dietrich didn’t look tough enough, Henry told the detective that he only had ten bolita writers in St. Pete but that with police help, “I can build up my force some more.” Dietrich jumped in with both feet, telling Henry that he was on board and would work to protect their interests and keep them informed of any investigations.

The following week, Dietrich took a call at his house from a Mr. Brown, who he recognized as Henry Trafficante. Henry asked Dietrich to come to Tampa for a meeting. The Hillsborough County Crime Commission’s director, Ralph Mills assisted Dietrich with his investigation. Mills drove to Tampa to stake out the meeting location, the Lamas Club on the corner of Gandy Blvd and Dale Mabry. Mills set up a camera and had his wife along for an additional set of eyes for surveillance of the meeting.

Dietrich bought a bus ticket and rode over to Tampa. Henry greeted Dietrich in the Lamas Club parking lot and led the detective to a waiting car. Dietrich got in the passenger side. Sitting behind him was Santo Trafficante Jr. Santo started by assuring Dietrich that the police could still make bolita busts in St. Pete but that they needed to concentrate those on potential competitors to the Trafficante operation. At that time, six other Tampa bolita bankers were operating in Pinellas County: Tony Martinez, Nick Sagonias, Virgilio Fabian, Doc Matthews, Jerry Lopez, and Rolando Rodriguez. Only Sagonias and Martinez were connected to the Trafficantes. Santo told Dietrich, “We have a good reputation in Pinellas and all over the state, and we want it to stay that way. We know that you don’t stay in business if you don’t pay off.” Santo parted ways with the observation, “We are supposed to be racketeers and gangsters, but we’re not as bad as they say.”

When Dietrich exited the car, Henry let him in on a secret. The yellow 1954 Mercury Sun Valley that Henry drove to the Lamas Club now belonged to Dietrich. And that was far from the only compensation the mob was willing to give Dietrich. Between January 5 and May 15, 1954, Dietrich received $1,275.00 in cash, a new suit, and two cases of whiskey. The meetings between Trafficante and Dietrich continued. The next time the two men met was at Wolfie’s Restaurant on Central Avenue in St. Petersburg. Henry handed Dietrich a list of ‘burg bolita sellers that were part of his operation and needed protection from raids.

On one occasion, Henry Trafficante came to Dietrich’s home. Dietrich’s daughter Janice, who was 12 then, recalled her and her mother hiding in a closet while her father and Henry spoke in the garage. According to Janice, a wire was attached to a recorder from the closet to a microphone in the garage, which was covered by an oil rag. At one point in the conversation, Henry picked up the rag and unknowingly uncovered the mike. But, according to Dietrich’s daughter, there was so much junk in the garage that Henry didn’t realize what he was looking at. The undercover operation was that close to being blown.

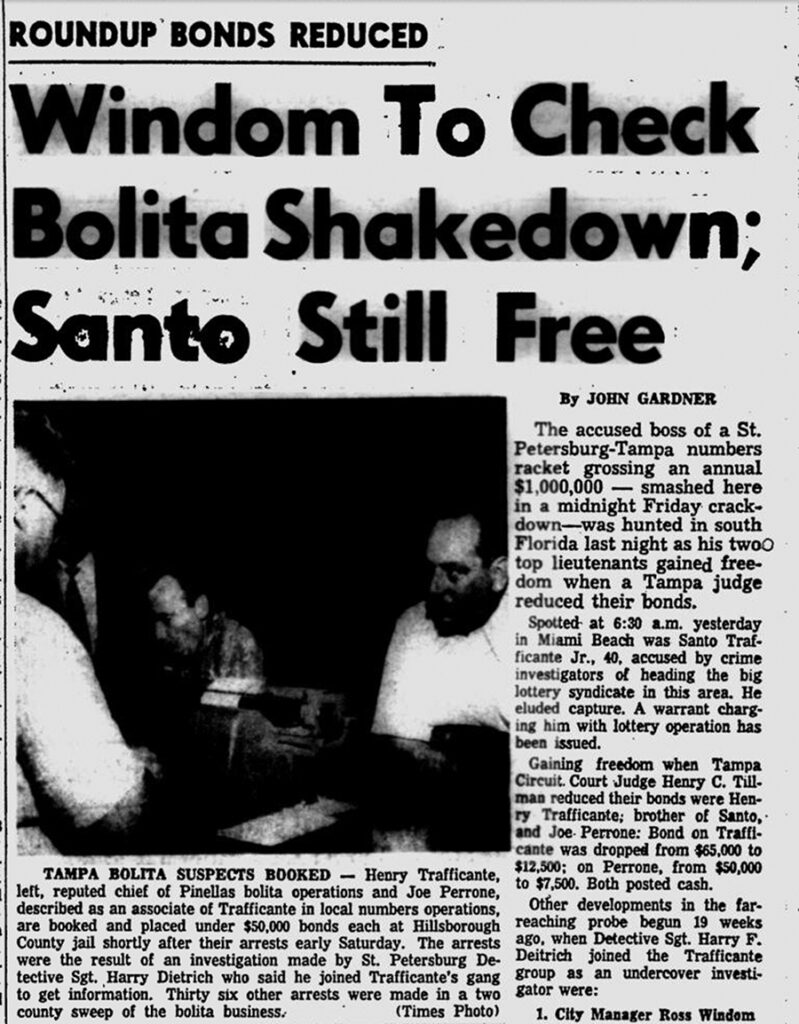

After recording 30 conversations, Dietrich went to his superiors and the State Attorney’s office to request arrest warrants. So, with warrants in hand, Dietrich pulled out of his undercover role. In the pre-dawn hours of May 15, 1954, Dietrich and the Hillsborough Sheriff’s Department assembled a hand-picked team of police officers and met in a Boy Scout meeting hall at the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church in St. Petersburg. Dietrich told the officers going into the suspects’ homes to rip out active phone lines in case they tried to warn others about the impending arrests. Over the next few hours, they arrested 43 individuals on gambling charges in both Hillsborough and Pinellas counties.

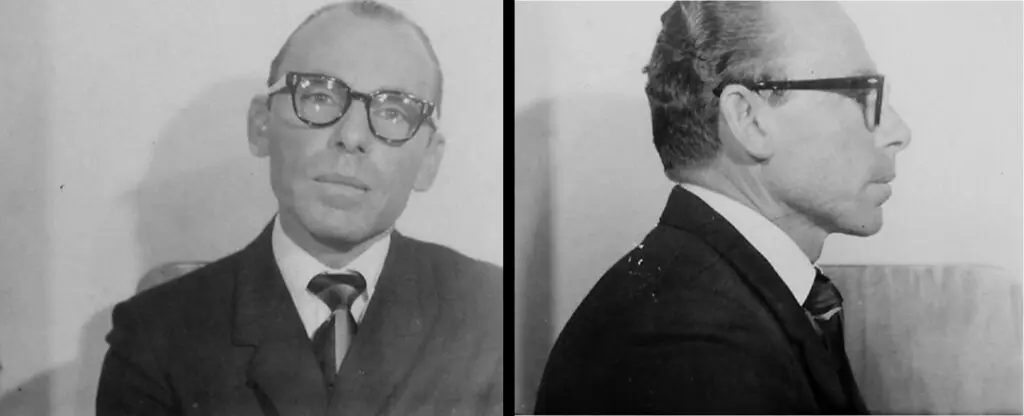

Henry Trafficante was arrested at the Nebraska Bar and Grill. Another Trafficante associate, Joe Perrone, was arrested while walking down a street in Ybor City. The bolita peddlers in St. Petersburg were also rounded up by the late morning. Henry Trafficante sneered at looming photographers but did not look particularly concerned.

At the steps of the courthouse in Tampa, Crime Commission director Ralph Mills bellowed a lengthy speech to reporters and curious onlookers. He claimed a sweeping victory against the Mob: “Arrests this morning in St. Petersburg and Tampa write another chapter, perhaps a closing one, on the widespread bolita lottery operations of the Tampa Trafficante Mob headed by Santo Trafficante, Jr.”

Rather than face a public arrest, Santo drove up from Miami to surrender to the Tampa police. Bail was initially set at $65,000 but then lowered it to $12,500. Trafficante quickly posted bail and was out on the street within a few hours to join his brother Henry, who had been released the day before.

Over the next few months, there were a series of pre-trial hearings. The Hillsborough County solicitor subpoenaed one of Santo Trafficante, Jr.’s men, Salvatore Lorenzo, who sat stone-faced in front of an interrogator who hammered him about his relationship to the Trafficante bolita organization. Frustrated, the prosecutor in the Trafficante case brought Lorenzo into court and swore him in, hoping that would make him loosen his lips. But Lorenzo declined to answer most of the questions. His refusal also earned him the nickname “Silent Sam.”

The first trial of Santo and Henry started in the fall of 1954. During that first trial, Dietrich’s family went into hiding until things cooled down. Dietrich’s work was vindicated when Santo and Henry were convicted of bribery. When the brothers returned for their sentencing four days after their conviction, they stood silently before Judge Victor O. Wehle while he called them “rats who crept out of the sewer to try and contaminate our country.” Both were handed a five-year sentence.

Their lawyers vowed to appeal, and in the interim, while the defense was preparing their appeal, Santo and Henry Trafficante were put on trial for a second time for violation of lottery rules in Pinellas County. This short trial wrapped up within a week; Henry was again found guilty, but the jury acquitted Trafficante because he was never actually in Pinellas County during Dietrich’s investigation. And on appeal of the first trial, Santo’s conviction was overturned.

A year after the initial raids, the U.S. Attorney General indicted Santo, Henry, and Joe Perrone, charging them with evading gambling taxes and gambling tax stamp violations. This was the third trial resulting from the Dietrich investigation. That trial ended in Jacksonville on December 12, 1959, with a conviction for Henry but an acquittal for Santo and Joe Perrone. The celebration was short-lived for Joe Perrone. Upon hearing of his release, he convulsed and died of a massive heart attack in the courtroom.

Though Santo Trafficante Jr. evaded prison, the crime family’s operations in St. Petersburg suffered a significant setback due to the Dietrich operation and the ensuing fallout. With what remained of their Pinellas operations under heavy scrutiny, the ‘burg was no longer seen as a cash cow for bolita. Many in local law enforcement put full credit on the undercover work of Dietrich. E. Wilson Purdy summed it up. “Harry did a good job with that. He nailed them.”

Detective Dietrich left the police department in 1964 after 22 years on the force. From there, he joined the Pinellas Public Defender’s Office, where he worked for another 21 years, retiring as their head investigator. He helped form the St. Petersburg Retired Police Officers Association and served as president of the local Fraternal Order of Police chapter. Detective Dietrich died on November 1, 1998, and is buried in Serenity Gardens in Largo.

Note: Mike Ward, an officer with the St. Pete Police Department, co-wrote this article along with Scott M. Deitche.

Scott M. Deitche is an author specializing in organized crime. He has written seven books and more than 50 articles on organized crime for local and national publications. He has been featured on the History Channel, A&E, Discovery Channel, AHC, C-SPAN and Oxygen Network. In addition, he has appeared on dozens of local and national news shows, as well as more than 40 radio programs. His latest book is Hitmen: The Mafia, Drugs, and the East Harlem Purple Gang. For more information about Scott, visit his page at HERE