THE CRACKER MOB IN FLORIDA

Harlan Alexander Blackburn died on October 21, 1998, of respiratory failure at a prison hospital in Minnesota. He was 79 years old and serving a 24-½ year sentence for dealing drugs out of a trailer park in Longwood. It was an unglamorous end to a colorful life. For over 40 years, even when he was in prison, Blackburn was the boss of a loosely knit crew of gamblers, moonshiners, drug dealers, and thieves called the cracker mob. They operated across Central Florida from Polk County across to Volusia, from Okeechobee County up into South Georgia.

But the mob that Blackburn ran had its roots in the early decades of the 20th century, in the sawdust joints and brothels that dotted the rural landscape of backwater Florida. From the turn of the 20th century, illegal gambling was already commonplace across Florida, buoyed by lax law enforcement in the smaller towns.

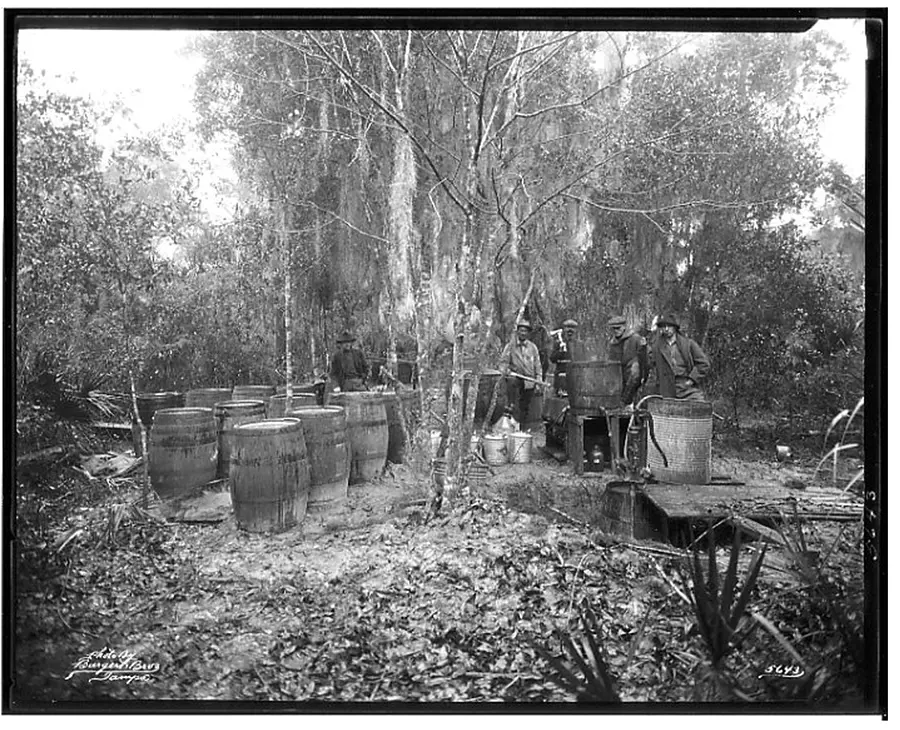

While gambling operators started coalescing into more organized groups and began to forge ties with organized crime elements in Tampa, it was the passage of the Volstead Act in 1919 that gave the fledgling underworld in Central Florida a substantial financial boost. Moonshine stills, which were already in operation, flourished. Most of Central Florida at that time was sparsely developed, so operations were still easy to hide. With Tampa serving as the port of entry for much of the raw materials necessary for the distillation process (sugar cane and molasses from Cuba) and farms providing grains and corn, moon shining became a massive part of the underground economy of Central Florida by the mid-1920s. And with the illicit alcohol production came a wave of more upscale establishments to serve up liquor and gambling to the populace.

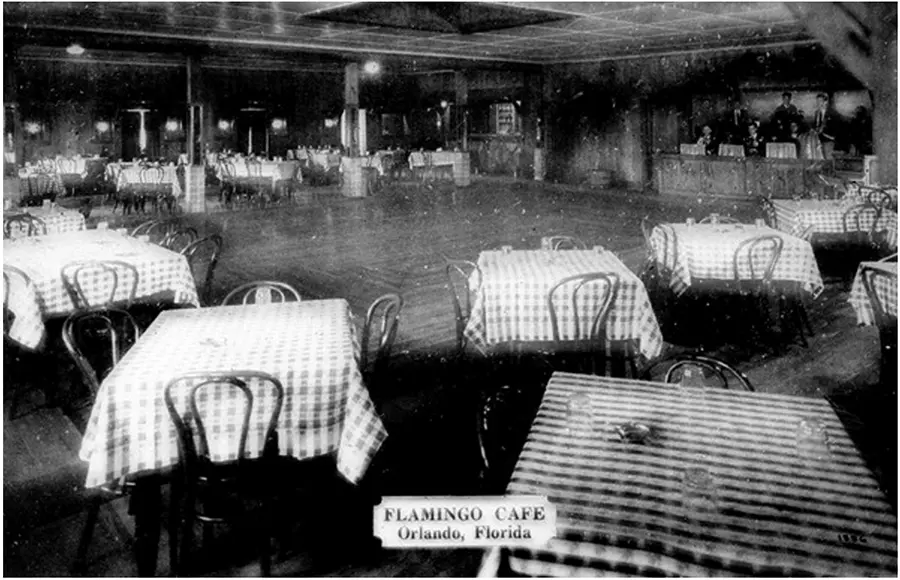

The Flamingo Cafe in Orlando opened in 1923, during the height of Prohibition. It was in unincorporated Orange County and occasionally patrolled by the Sheriff’s Department. After the Volstead Act was repealed, the club maintained its status as a top-flight place for nighttime entertainment. This was helped by the back room, where patrons were graced with roulette wheels and card games.

One of the most notorious clubs in Central Florida was The Paramount Club, located on Tampa Road, about three miles west of Lakeland. The Paramount was a gathering place for some of Central Florida’s most notorious gangsters, like Ed Milam and the club’s owner, Rhodes Boynton. They both operated sizable bolita and bookmaking operations throughout the rural counties. Charlie Wall, the gangland boss of Tampa at the time, was also a regular at the Paramount and cemented Tampa underworld ties with the “crackers” that would continue for decades to come.

One of the bolita peddlers who frequented the Paramount was Henry Hull. On the night of October 26, 1939, Hull walked out of the Paramount with $560–$300 for winners on his bolita tickets and $200 profit. The following day, a truck driver passing through Zephyrhills noticed a burning car off the road. It was Hull’s. Then, on Sunday, October 29, two fishermen came across Hull’s body in the Hillsborough River near Temple Terrace. Hull was killed by three bullet shots to the back. His killer bound the body in wire, attached some heavy weights, and dumped him in the river. Hull had two bolita tickets in his pocket. Interestingly, his body was discovered just two weeks after mobster Mario Perla was gunned down on 15th Street in Ybor City.

Several Paramount Club regulars were held for questioning, including Ed Milam, Rhodes Boynton, and Tony Martinez, who was based out of Tampa. All the men were released, and the murder, like many other gangland killings at that time, went unsolved. The Paramount Club closed down, but the illegal operations continued. The cracker mob rose from the ashes of the Paramount Club, with gangland figures spreading out across Orange, Seminole, and Osceola Counties.

Ed Milam moved to Orlando after the Paramount Club closed and became a well-established bolita operator. But he got a little too big and successful. At about 4:30 in the afternoon on Monday, May 11, 1953, Milam received a call at his home. He told his wife he was going out and would be home in two hours. Milam drove over to the Chapman Fruit Company in Orlando. He exited his car, entered a dark blue 1950 Ford with two other men, and drove off. That was the last time anyone saw Milam. Six days later, on May 17, an army sergeant and his wife were collecting swamp cabbage in Reedy Creek swamp, about ten miles south of Kissimmee. They came upon Milam’s body in a ditch. He had been shot three times in the chest, and his face was torn up. Police later determined that the body was killed elsewhere and dumped in the swamp.

It’s not known who killed Milam, but it’s pretty clear who ordered the hit. By the time of Milam’s death, the head of the cracker mob’s operations was Harlan Blackburn. And in the wake of Milam’s demise, Blackburn’s star in the underworld was clearly on the rise.

Born on April 13, 1919, in Orlando, Blackburn was a well-known figure to police before he rose to the top of the underworld heap before World War II. Blackburn served during the War, making money from black market sales, and hit the ground running when he returned to Orlando. He hooked up with Clyde Lee, a trusted lieutenant, in 1948. Lee later told police that the gambling operations were bringing in up to $100,000 a week at times.

Blackburn’s power was not only derived from his corrupting of law enforcement and political connections but also from his relationship with the Tampa Mafia. The connections between the Tampa Mafia and the cracker mob were so numerous it’s safe to say that the two crime organizations were integral to each other’s gambling operations in many parts of the state.

Many notable Tampa underworld figures worked with Blackburn and members of his crew. Joe Pelusa Diaz ran a bolita operation in Tampa and Winter Haven, along with Jimmy Fraterrgio and Raymond Rodriguez. Diaz’s operation used some of Blackburn’s sellers in Winter Haven. Dominick Furci oversaw gambling operations in Brooksville with some of Blackburn’s guys. He would drive up on the weekends to take bets. Sam Cagnina was arrested with members of Blackburn’s Polk County crew. Al Scaglione resided in Lakeland and operated the Italian Castle restaurant at 1801 New Tampa Highway, where FDLE reports indicate members of the cracker mob would operate.

In the late 50s and early 60s, the cracker mob’s tentacles reached up into Georgia, where they provided lay-off services from local gambling figures in the Peach State. An FBI informant told the Bureau that Rudy Mach, a Moultrie gambling kingpin, laid off bets to Blackburn in Orlando, who in turn laid off his bets to Trafficante. Blackburn’s group also intersected with members of the loosely affiliated Dixie Mafia in such gambling-rich locales as Phenix City.

Though he was a gambler by profession, Blackburn was not incapable of violence. Jack Butler oversaw Blackburn’s gambling in Daytona Beach. In 1957, word began to spread that in addition to not only consistently betting away his profits, but Butler also wanted to cut off ties with Blackburn and forge an alliance with the Dixie Mafia, bringing them into the Sunshine State. On the night of December 11, Butler and his wife were gunned down in their Daytona Beach house. Though unsolved, the consensus was that Blackburn took care of Butler, cementing his hold over the cracker mob.

Like Santo Trafficante Jr., Blackburn was the undisputed kingpin of his empire. But in one essential aspect, Blackburn differed greatly. He got arrested…a lot. While Santo Trafficante Jr., never spent a night in jail, Blackburn spent a good chunk of his life in prison. He was arrested numerous times in the 1940s and 50s, for gambling and other crimes.

On October 19, 1963, the FBI arrested Blackburn and two of his top lieutenants, Joe Wheeler of Orlando and William Strawder from Sanford. They were charged with not having a gambling stamp and a number of minor gambling charges. The constant law enforcement pressure on Blackburn’s operations did little to dissuade the gangster.

In November of 1962, Blackburn was arrested as part of a gambling sweep that also netted Ralph Strawder, one of Blackburn’s top associates. The gambling operation was said to have brought in over $200,000 a week.

A few years later, Blackburn’s organization was at its peak. Police estimated that in 1971, Blackburn had about 20 bolita bankers and 200 sellers in his organization. But by the mid-1970s, that number was cut in half due to not only law enforcement pressure but by the changing nature of illegal gambling away from bolita and the fact that Blackburn was in prison for the first part of the 1970s due to a one-two punch of a tax evasion charge, and a conviction for setting up his right-hand man Clyde Lee, for a botched assassination attempt off I-4.

After his parole in 1975, Blackburn began dealing marijuana but was arrested for that in 1976. After his release on the marijuana charges, Blackburn traded up for cocaine and a federal sentence for trafficking in 1981. Four years later, Blackburn was paroled again. By this time, his organization was just a memory. Many of his former colleagues were dead or out of the business. But that didn’t stop Blackburn from turning to crime. In mid-1990, Blackburn was arrested at his home in rural Seminole County when authorities found traces of cocaine. He was sent back to prison but paroled again in 1992. He started dealing cocaine, grossing over $10,000 a week. But his new business venture was short-lived after an associate was arrested for dealing. He was sent back to prison with a 24-year sentence.

When Blackburn died in 1998, with him went the cracker mob, an integral part of the history and lore of Central Florida.

Scott M. Deitche is an author specializing in organized crime. He has written seven books and more than 50 articles on organized crime for local and national publications. He has been featured on the History Channel, A&E, Discovery Channel, AHC, C-SPAN and Oxygen Network. In addition, he has appeared on dozens of local and national news shows, as well as more than 40 radio programs. His latest book is Garden State Gangland: The Rise of the Mob in New Jersey. For more information about Scott, visit his page at HERE