AL CAPONE’S TAMPA BAY CONNECTION

Few gangsters loom larger in pop culture than Alphonse Capone. Though his reign over the Chicago underworld was brief, it lived on through the years, gaining a legend-like status. Capone was a brash, press-savvy gangster, and the public ate it up. He hobnobbed with celebrities of the day and showed a humanitarian side by providing food and clothes for down-on-their-luck Chicagoans during the Depression. Still, most of all, he thumbed his nose at the National Prohibition Act, which enforced the 18th Amendment (commonly known as Prohibition), a law that many in the United States broke regularly.

Al Capone’s ties to Florida are well-known. His last years were spent on his estate in Palm Island, near Miami. He frequently visited South Florida during his heyday. Photographers went everywhere he went. What is less well-known was his time and his investments in St. Petersburg. Capone, along with some legitimate business partners and the expected underworld partners, owned a good deal of property in the ‘burg and other areas around Pinellas.

Locally, Capone’s urban legends and stories in Pinellas have been around for decades. Many of the area’s top hotels, including the Don CeSar and the Vinoy, claim Capone as one of their guests. He was a big baseball fan and a friend of Babe Ruth. Sightings of Capone at spring training games were common, and he frequented some of the area’s speakeasies.

There was an article in the Tampa Bay Times (formally, St. Petersburg Times) about a house on Shore Acres, guarded by two stone lions, supposedly owned by Capone. Capone allegedly had the house built in 1925 for his mother. There is also a large brick house on 22nd Avenue South, near 16th Street, in St. Petersburg, that also at one time was either built or owned by Capone, according to lore.

These houses do not appear on county property records as being owned by Capone. That certainly doesn’t mean he didn’t have a financial interest in them or that he never lived in them for a time, just that the official record is lacking. There are, however, several parcels that were owned by the Chicago gangster outright.

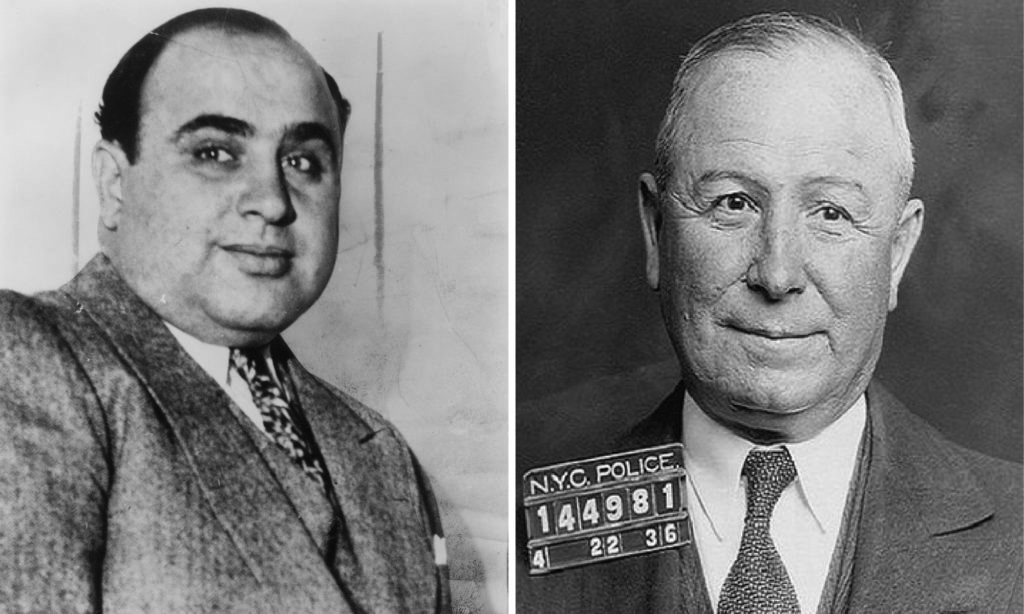

Capone’s parcels were part of a joint venture with three other men under Manro Corp. The first partner was a real estate agent, Jack Vanella. There is little known about Vanella other than he represented Capone’s interest in several properties in Pinellas and was listed on the deeds. Another partner was Jake Guzik, better known to his underworld cohorts as “Greasy Thumb.” Born in Moscow, Greasy Thumb was one of the major political fixers for Capone in Chicago, greasing the palms (hence his nickname) of politicians, judges, and police. The last of the partners was Johnny Torrio, Capone’s mentor in organized crime and a major mob figure in Chicago before he left the Windy City and handed over the reins to Capone.

Capone’s land deals in Florida coincided with the 1925 land boom that brought speculators, investors, grifters, and marks down to St. Petersburg to participate in what eventually became a massive bubble. The largest parcel in St. Petersburg was a 28-acre tract in South St. Pete/Gulfport, which now is the site of the Twin Brooks Golf Course. Capone was reportedly interested in land Torrio owned in downtown St. Petersburg, near a speakeasy known as the Green Cabin. The Cabin sat on land that was eventually turned into the American Legion Hospital for Crippled Children in 1927. Capone also owned a large tract that spanned from 22nd Avenue South to 28th Avenue South and 38th to 41st Street, near Gulfport.

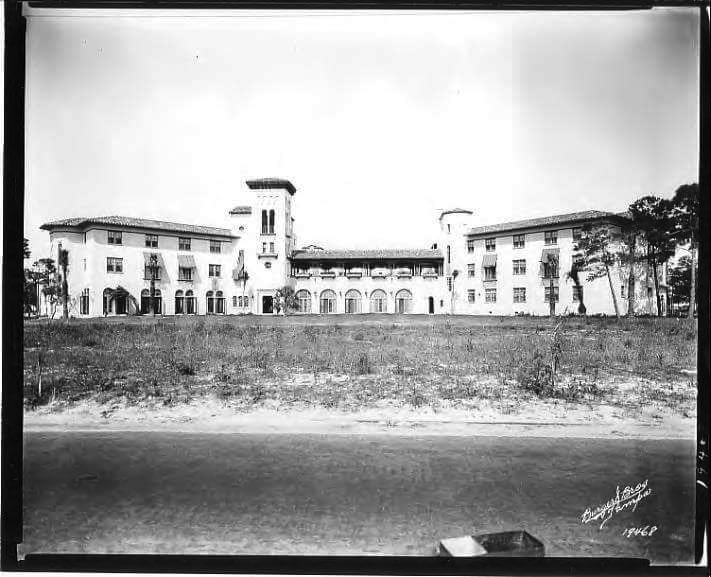

Capone also spent time on the city’s far west side when he came to St. Petersburg. His men would stay at the Jungle Prada Hotel, now Admiral Farragut Academy. Capone frequented the Gangplank Club, now the Max and Sam’s Bar & Grill site, and just up the road from Admiral Farragut on Park Boulevard. In the restaurant sat a safe, which legend has it, contained valuable papers of Capone’s. But throughout the years, no one attempted to open it. In early 2011, on an unaired episode of the (now-canceled) Discovery Channel show American Treasures, the show’s hosts open the safe only to find it empty, much like Capone’s vaults were when Geraldo opened them in the 1980s. Nonetheless, Capone’s place in the lore of the Jungle Prada area is secure.

While Capone wined and dined in St. Petersburg, what’s interesting is that there is no evidence suggesting any meetings or joint criminal enterprises between Capone and the underworld in Tampa. At the time Capone was frequenting St. Petersburg, the underworld in Tampa was under the control of Charlie Wall. The fledgling mafia was getting their bearings under guidance from Ignazio Italiano and early mob figures like Giuseppe “Joe” Vaglicia; bootlegging was big business, especially in Ybor City.

In addition to liquor being brought in through the Port of Tampa, there were shipments of corn sugar, molasses, and other raw materials made into moonshine in the thousands of stills scattered throughout rural Hillsborough County and into surrounding areas. It would have been a genuine interest to Capone, but without evidence that he met with local mob leaders, it would only be wild speculation. In the mid-1930s and into the early 40s, the Tampa mafia began cementing their relationships with Chicago, and the main commodity was narcotics.

In St. Petersburg, Capone’s real estate ventures started falling apart in the 1930s. He managed to avoid the major real estate bust, but other issues were complicating his property investments. Capone needed to be in shape to manage the properties actively; he was sentenced to 11 years in prison in 1932 for income tax evasion. In 1936 the feds filed a tax lien against the Twin Brooks property. It was sold off a few years later. One of the Capone properties, a 10-acre plot in the 1300 block of North Disston Boulevard in St. Petersburg (now 49th Street), resulted in a civil case relating to the non-payment of the mortgage.

The note holder sued Capone and his partners for $250,000. By the time the case went to trial in 1942, Vanella had died, and Torrio and Guzik had evaded subpoenas, leaving only Capone to fight the charges. On March 17, 1942, a circuit court jury in Clearwater handed down a verdict in favor of Capone.

But by that time, Capone’s health was in decline. Although he was paroled in November of 1939, his days as a crime kingpin were over, and he was spending his time on his estate in Palm Island. Al Capone died on January 24, 1947.

While Capone’s land deals were a memory by then, Johnny Torrio, his mafia mentor, was still buying and selling property throughout St. Petersburg and the beach communities. At any given time, Torrio owned over a dozen properties in Pinellas County, including parcels on Pass-A-Grille, where he lived for a while in the late 1930s (though he listed his home address as Brooklyn).

But it wasn’t until 1950 that the extent of some of his dealings became publicly known. That December, the traveling mob-busting Congressional investigation known as the Kefauver Committee had brought its fact-finding mission to Tampa to investigate the corruption between the Tampa mafia and local politicians and law enforcement. Some time was made to discuss Johnny Torrio. The investigators were particularly interested in the sale of a parcel on Pass-A-Grille, which was sold to Hillsborough County Sheriff Hugh Culbreath on December 21, 1944. The real estate agent who brokered the deal told the Kefauver Commission:

“There is a record of the closing or sale of the Pass-A-Grille property by John Torrio and wife to Hugh L. Culbreath and wife, showing ‘the purchase-price credit and deposit paid, which was $1,600, and received from the purchaser so much money and marked “collected $1,600″ by Tracey.”

Culbreath’s dealing with Tampa mobsters was the main thrust of the Commission’s inquiry into his financial dealings. They were trying to ascertain how he managed to own too much property on his salary. During the hearings, former bolita dealers told of underworld payoffs to Culbreath, who earned the not-so-flattering nickname “Cabeza de Melon” (melon head in Spanish), among the underworld denizens who kicked up money to him and others in the Sherriff’s Department. But it was attractive to the Congressmen that Culbreath also managed a deal with Torrio. What was also interesting was that Pass-A-Grille property was right near a fish house owned by Salvatore “Red” Italiano, a major mafia figure in Tampa and known associate of Culbreath.

After the Kefauver Commission, Torrio unloaded most of his properties and returned to Brooklyn, where he died in 1957. With Torrio’s death, the gangland era of Capone was drawing to a close. However, while the legacy of the Chicago mob presence in Pinellas County was over, the attachment of the respective crime organizations in Tampa and Chicago grew. As the era of Al Capone and Johnny Torrio faded, the criminal partnership between Santo Trafficante Jr. and Chicago mob boss Sam Giancana began.

Scott M. Deitche is an author specializing in organized crime. He has written seven books and more than 50 articles on organized crime for local and national publications. He has been featured on the History Channel, A&E, Discovery Channel, AHC, C-SPAN and Oxygen Network. In addition, he has appeared on dozens of local and national news shows, as well as more than 40 radio programs. His latest book is Garden State Gangland: The Rise of the Mob in New Jersey. For more information about Scott click HERE