BOLITA VICE SQUAD

The winning bolita numbers were that week’s winning Cuban lottery numbers, which were drawn in Cuba at 1 p.m. on Saturday. Everyone involved in bolita in Tampa, from the players on up, “listened to a Cuban radio station at 1 p.m. for the winning numbers. At 1:01 p.m., the Call-In Guy would gather all his bolita tickets, place them in an envelope, walk to a specific street, and look for one particular car. The Call-In Guy nonchalantly handed the driver (D1) his envelope when the car slowly drove by. The Call-In Guy’s job was done for the day, and he had no idea where the driver was going. D1 collected from all the Call-In Guys in a specific territory. Once he had collected from all his Call-In Guys, he drove down a particular street and looked for a specific car. When the two vehicles cruised by one another, D1 handed his envelopes to the other driver (D2). D1’s job was done for the day, and he had no idea where D2 was going.

The process repeated five to eight times in each territory, each driver handing his envelope to another driver, never knowing where the new driver was going. Finally, the only driver who knew the final destination of the envelope was the last driver, who then took the envelope to the “Drop House,” where bolita tickets from numerous Call-In Houses and up to dozens of peddlers were delivered and calculated. The money went through the exact process but was taken to another house. The tickets and cash were kept separate so that if one was busted, the other was safe.

Clifton’s Sicilian source helped him crack the mazes and provided him with the names and addresses of numerous bolita dealers. Meanwhile, the family tree helped Clifton identify the major players in town.

“Ellis was everywhere,” said Meisch. “[The bolita dealers] called him the rabbit because he was always popping up all over town.”

“One Saturday, Charlie Whitt [a third partner] and I and Ellis went to a local grocery store in Ybor City, “I can’t remember which one “because we knew they were selling bolita [and knew it was also a Call-In House]. The numbers were called in at 1 p.m., so we’d wait until 1:01 p.m. to make a bust because we knew the bolita tickets would be scattered on a table so the numbers could be tallied. So we went to the store, and we went up to the front door, and an old man was coming out, and when he saw us, he hollered, “Tres Conejos.” So we went in, and the old man who owned that grocery store was scrambling to get rid of his bolita tickets. Well, we realized that tres is three and Conejo is a rabbit. So the old man yelled, “The three rabbits,” tipping them off that we were coming in. After a while, we were referred to as the three rabbits.”

The Vice Squad often cut deals with those they arrested for information in exchange for less or no jail time. If the prospect of jail time didn’t scare them, the Vice Squad would bribe the answers out of them. The Sheriff’s Office had a fund called “The Emergency Fund” that was earmarked for such bribery. If the peddler or driver gave them information that led to a small bolita raid, they were paid a few dollars. But, if it turned into a significant raid, they’d be paid $200, a lot of money for a nickel and dime bolita peddler or driver to earn in the 1950s.

The more information they received, the more frequent the busts became. “It seemed like we were busting somebody on gambling charges every Saturday,” said Whitt. And with each bolita bust, the Vice Squad gathered more information, leading to more and larger busts.

Usually, a peddler would provide Clifton with the Call-In House number. Clifton and his men would track down the owner of the phone number and stake out the establishment. Clifton and his crew would follow him and begin tracking the maze of exchanges when the Call-In Guy would leave to deliver his tickets to a driver. Once the maze was documented, they’d return the following week to arrest everyone who was part of it. The arrests had to be quick and well-planned, though.

“The bolita numbers were often printed on cigarette paper,” explained Whitt. “That paper was easily flammable and would burn quickly if the cops walked in.”

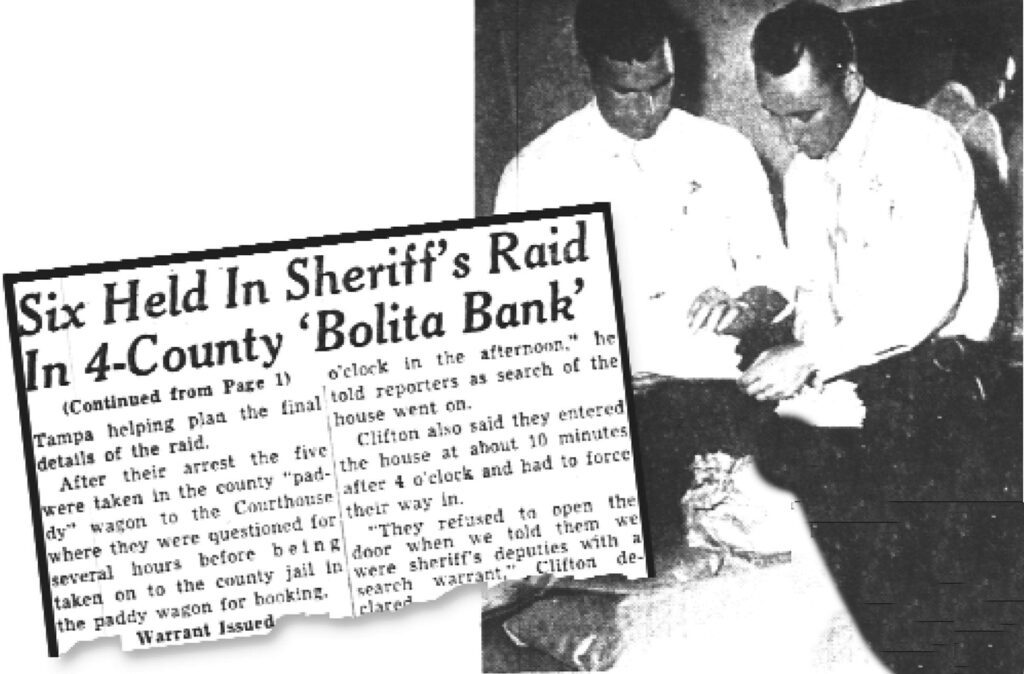

Despite all this activity, after months of arrests, a $200 reward for a huge bust had yet to be paid. Some of the bolita busts were big, but none were major. Then, in early 1958, Clifton found himself yet another informant looking to earn a few dollars, and the new informant provided him with information that, while worth $200, was priceless. The informant told Clifton specifics about a maze of bolita tickets that began in St. Petersburg every Saturday and included bolita tickets for Hillsborough, Pinellas, Manatee, and Polk counties. This was the most extensive bolita maze Clifton had been tipped off on. So the following Saturday, Clifton got to work.