THROUGH THE EYES OF A DAUGHTER: THE HIT ON JIMMY VELASCO

Jimmy Velasco was a political fixer. He was the lynchpin in Tampa between the gambling syndicate and the corrupt public officials who turned the other way for a cash-stuffed envelope. Velasco controlled the elections and worked the payoffs to ensure that the various bolita operators, himself included, could make a living with minimal interference from law enforcement.

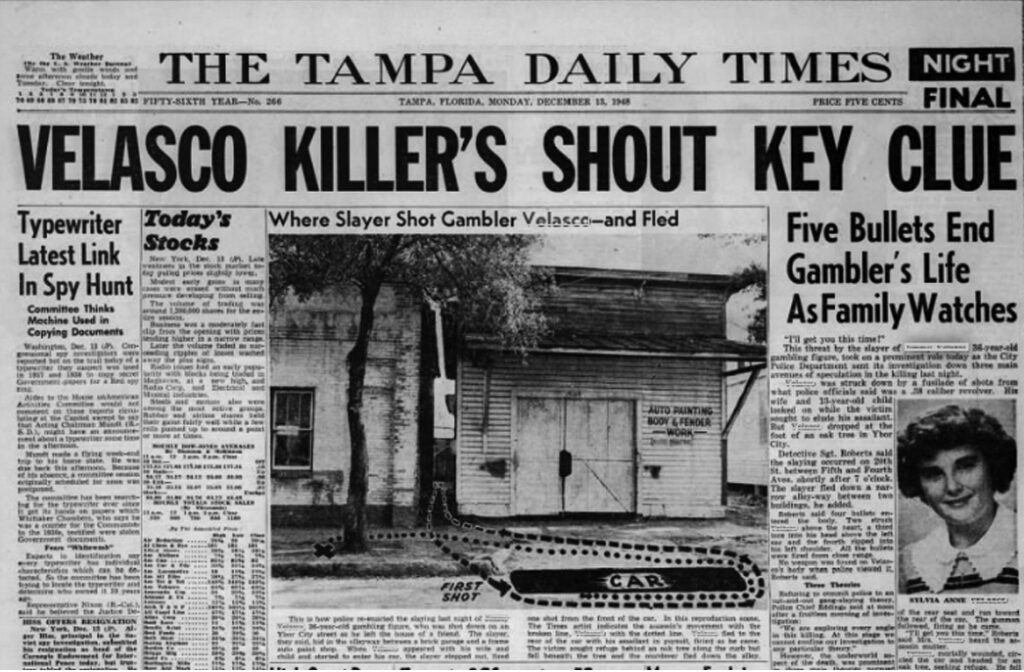

But as the Mafia began to flex its muscle in the Tampa underworld, Jimmy felt himself getting squeezed. As his daughter recounts, “He was here first. Then, they moved in and muscled him later.” And on Sunday night, December 12, 1948, Jimmy became the victim of Tampa gangland violence in one of the most significant underworlds hits in Tampa history, which had repercussions far beyond Cigar City.

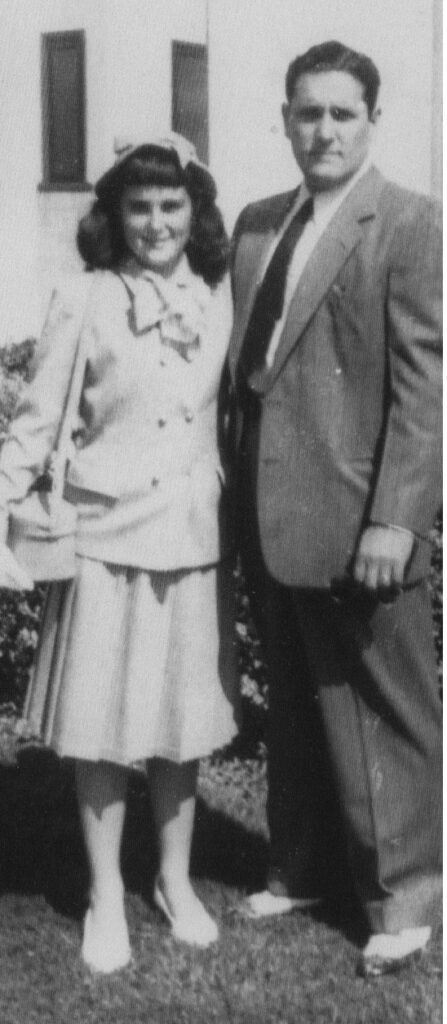

Jimmy Velasco was killed in the presence of his wife and daughter, Sylvia, violating the general Mafia protocol of not involving family members in the violence. And now, the true account of Jimmy’s last day is told for the first time.

Tampa Mafia Magazine sat down with Sylvia Velasco to talk about her father and her first-hand account of his killing. She was joined by her cousin Dennis Velasco, son of Jimmy’s younger brother Arthur, who relayed stories of his dad’s quest for vengeance against the Mafia and corrupt City officials in the wake of Jimmy Velasco’s death.

“My dad, Jimmy Velasco, was born in Key West, as was his father, Rojelio. In the old days, the cigar industry was Key West, but it was too confined. So the cigar business came to Tampa, and my grandfather followed. My dad also went to Hillsborough High School and met my mother here.

“When I was 3, going on 4, at the tail end of the Depression, we went to California. My father and two of his cousins put up a gambling ship off the Redondo Beach pier past the three-mile limit. It was called the Lux. He needed people to work the gambling ship, so the men went out first. Ralph Reina went out as well. They all went to the Redondo Beach area and worked the gambling ship. The women sometimes went out on the ships as shills. What happened was that Earl Warren, the attorney general of California, bribed the ship’s pilot to bring it within the three-mile limit and raided the ship. The ship was then closed, so they were out of a job. My Dad had a 1938 Chevrolet. We had a small trailer and drove back to Tampa, four adults and me in the car. We ran out of cash, so we’d stop and sell some clothes to gas up the car and buy food so I could eat. Once we got back to Tampa, we were okay.”

From there, Sylvia lived a relatively everyday life in Tampa. “We lived in Seminole Heights near Hillsborough High School. I went to Sacred Heart Academy. I had a very normal life. We were probably a little more affluent than many people. But my life didn’t have anything to do with my father’s. My mother was cautious about not exposing me to any of this. She did not want me in that environment.”

But Sylvia knew many of the prominent organized crime figures in the 1940s. “The three men I saw regularly were Augustine “Primo” Lazzara, Salvatore “Red” Italiano, and Gus Friscia. I don’t remember Santo Trafficante Jr. I would hear about people like, Jimmy Lumia, Frank Diecidue, Rene Nunez, those kinds of names.”

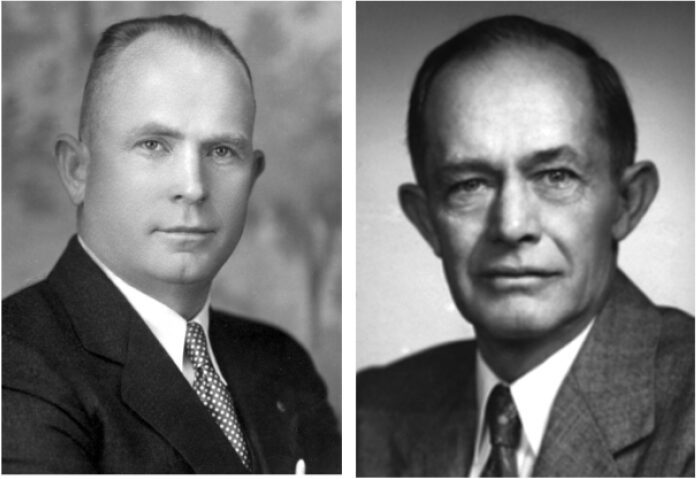

“We used to go visit Mayor Curtis Hixon a lot. My Dad would go into the house, and my mother and I would sit in the car. It was so hot, and there were mosquitoes. Hixon was probably the one my Dad met in person often.”

Sylvia then recounted the night of the shooting. “It was Sunday night. We’d gone to the show earlier and stopped by Cheecho’s house (brother-in-law of Paul Antinori Sr). Cheecho lived upstairs, and Paul and his wife lived downstairs. We went up because my father was going to check on bolita. It was the eve of St. Lucy’s Day. So we had a drink that the Italians consumed that night. It was sweet, and it had barely in it. It was supposed to be for good eyesight. I still cannot eat barley to this day.

We were descending the steps to the Buick my Dad had just bought. We crossed the street, and my mother went alongside the car. There was an alleyway near us. My mom was getting in on her side, and my dad was getting in on his side. My door was open, and his door was open. I was standing there; his gun was on the car seat because he had left it there.

I heard this noise and said, “Daddy, firecrackers.” And all hell broke loose. And that’s when I looked, and I saw this guy wearing a hat and coat, and he was in the front of the car and started to shoot. The gunman grabbed my mom and used her as a shield first. My Dad didn’t have time to get to his gun. Everything happened so fast.

My father comes and shoves me in the backseat. I got up on the seat, looked, and watched the whole thing. Then the guy took off. My mother was screaming. I got back out because I saw my father was down.

I grabbed my father and started screaming. “Daddy, daddy.” He wasn’t gone yet. All the adults came streaming out of the house and ran to my father. They all put him in a car, took him to the hospital, and left me sitting there. All the adults went to the hospital. So I crossed the street. I wasn’t nervous. I was collected. I walked across the street to Paul Antinori’s and asked if I could use the phone. I called my Uncle Art. He wasn’t there. But my aunt answered, so I told her what had happened. I said we were at Cheechos, and they took my father off. I told her to tell him what happened and tell the brothers.

My mother came back in a car. I don’t recall if it was our Buick or someone else. This part is vague. And we ended up at the police station. We were sitting in a waiting room, and I didn’t know my father was dead. I’m not sure if they took my mother or me first.

Police took me in for questioning without an adult; I was 13 then. So they took me in that night. So I told him what had happened. And he said okay. And then he got on the phone, and I heard him saying, ‘take the body to such and such place.’ So I asked him if my father was dead, and he said yes.”

What was it like for you afterward?