BOLITA VICE SQUAD

In March of 1958, Buddy Meisch, a young hard-nosed ex-Tampa cop turned deputy, had been with the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office Vice Squad for over a year. He grabbed his binoculars and stared at his target located 100 yards away. It was the Ybor City home of one of Tampa’s most notorious gangsters, Frank Diecidue, the underboss of the Santo Trafficante-led crime ring that controlled the city’s underworld.

Meisch’s radio squawked, “Homerun.” That was the signal for which he had been waiting. He looked back to the target’s home. Numerous law enforcement officers, with guns ready, began to creep towards the house. The head of the raid stood before the front door and casually knocked.

History was about to be made. The evidence was inside that home: thousands of bolita tickets collected throughout multiple counties enough to deliver a crippling financial blow to the Trafficante empire and, perhaps, finally, a charge that could stick to Santo Trafficante and put him in jail for a long time. Finally, the months-long investigation was about to come to fruition.

As if on cue, a rat scurried across the warehouse floor. Ironic, thought Meisch; this entire raid was due to rats in the mafia, and the Vice Squad had to plan the raid knowing that rats in the Sheriff’s Office could have compromised it at any moment.

In the early 1950s, Captain Ellis Clifton didn’t know the definition of fear. Perhaps because it often seemed he had an angel on his shoulder as he never suffered any consequences, no matter how dangerous his job became.

He had been head of the Vice Squad’s Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office’s department charged with bringing down the Tampa Mafia- since 1953 and had survived his fair share of threats. Thousands of dollars in bounties had been put on his head, yet no one dared to collect. He had been followed by gangsters as though they were the police and he was the criminal, yet nothing ever came of the pursuits. He had raided dozens of bolita parlors and walked away from each unscathed. Yet, in the early 1950s, he was shaking when he sat in his car parked on a desolate road in the middle of Tampa’s boondocks with a known Sicilian felon seated next to him. The shakes were not from fear, though, but from excitement.

Just a few days earlier, Clifton busted the Sicilian committing a crime. But, rather than arresting him, he made a deal. If the Sicilian would meet him on a desolate road at a specific time in a few days and tell him everything he knew about Tampa’s underworld, he would let him go. The known felon agreed. He provided Clifton with a family tree! A who’s who in the Tampa underworld with an understanding of how the gambling operations were run.

“I finally got a Sicilian guy, and I told him I would lay off him if he would talk to me for six months,” explained Clifton. “So I got me a legal pad and got him in the car with me, and we talked for five hours.” Clifton would never reveal the source, though. Not even over 50 years later, knowing he would soon succumb to cancer.

“This illegal lottery flourished in Tampa and earned the mafia millions yearly.”

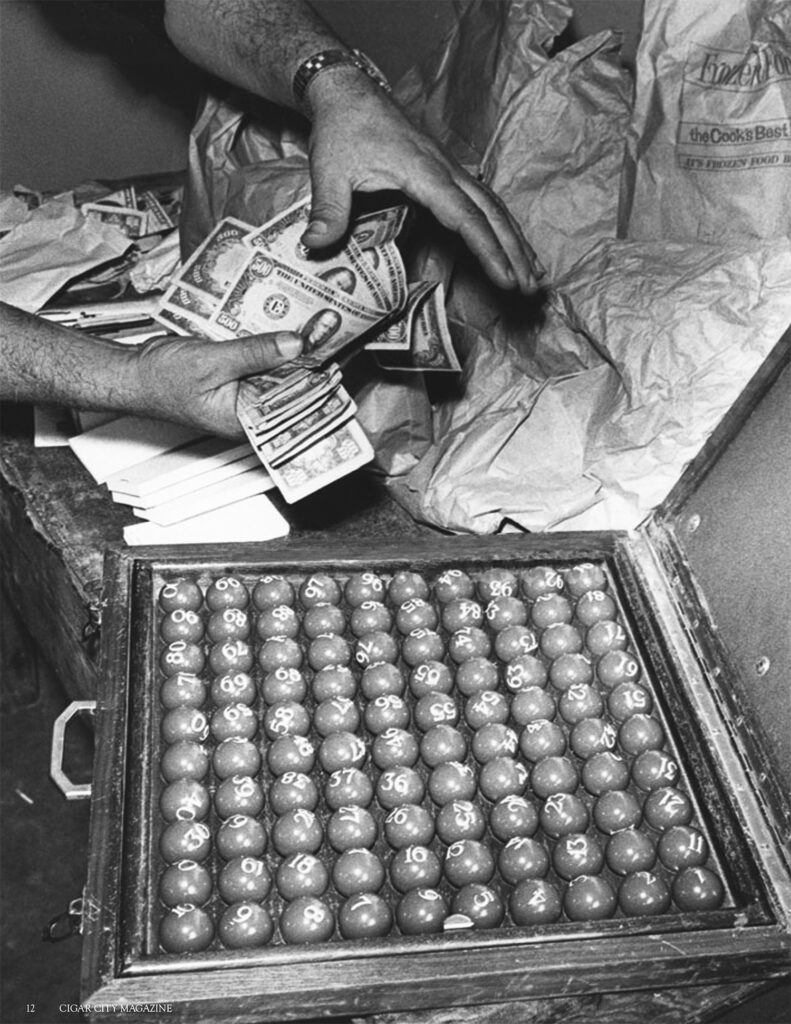

As the Sicilian felon bared his soul, Clifton understood why it had been so difficult to make any significant headway in the Sheriff’s Office’s war on bolita. This illegal lottery flourished in Tampa and earned the mafia millions yearly. Sure they had made dozens of small bolita busts, but nothing earth-shattering. Moreover, they could never find where a major haul of bolita tickets or money was counted. The reason: the Sicilians knew what they were doing. The tickets and money for major bolita rings were each separately run through a maze of bureaucracy and multiple hand-offs until they reached their final destinations, making them hard to follow unless law enforcement had insider information.

According to Clifton’s new Sicilian source, the maze started with the street peddlers, also called “writers.” Some of the street peddlers sold numbers on the street corners, while others may have sold numbers from an establishment they owned a restaurant, cafe, bar, hardware store, etc. Once the player made his bet, the peddler gave the player a ticket with the number he played printed on it. The peddler then called a “Call-In House” and read the “Call-In Guy” the numbers he sold and to whom, and the Call-In Guy would write up tickets for each sale for his records. But, of course, the peddler rarely knew who the Call-In Guy was; he only knew what phone number to call.